Ladies' Clothing underwent a number of

stylistic changes during the 18th century; a few dramatic but mostly subtle.

The following little article is an introductory overview, not an exhaustive

guide. Please do research on the exact decade and type of person you would

like to portray.

Lord Scott

Outer Garments, The Gown and Associated

Articles:

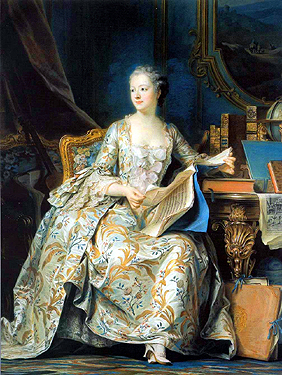

There were several different cuts and styles

of ladies’ gowns during this period. The “Robe a l’Anglaise” (English gown,

mantua) and “Robe a la Francaise” (French gown, sacque, sack back gown) were

perhaps the two most common gown styles for most of the century though each

went through a number of variations and adaptations.

Ladies gowns were composed of several basic

pieces. The bodice (aka “pair of bodies”) covered the back, shoulders, sides

and left and right front. It was quite fitted. Sewn onto the bodice were

fitted sleeves of about ¾ length which often sported fabric or lace flounces

at their ends. In the front, center was worn the stomacher. This was a firm,

stiff article which covered the stomach and lower bosom (styles tended to be

low cut by modern standards) and attached to the bodice by means of pins,

laces or hooks and eyes. A square piece of linen or cotton cloth known as a

"fichu" was often folded and worn around the neckline for daywear.

The skirt was sewn onto the bodice and hung

nearly to floor length (longer if a rear train was desired). It covered the

back but was open in the front to reveal a petticoat. (A gown which did not

open in the front was called a “round gown.”) This petticoat was a skirt

which was meant to be revealed (in contrast to petticoats used as underwear)

and like the stomacher was of a fabric which either matched or made a

pleasant contrast to the gown.

During the 1770s it became a popular option

to bunch or drape the skirt up somewhat on the sides and/or rear. This style

was known as “a la Polonaise.” About the same time a style of bodice emerged

which closed in front without the use of a stomacher.

An alternate outfit common to working women

or used as day or casual wear by more leisurely women would consist of a

jacket, skirt and petticoat. The jacket was, in effect, a replacement for

the bodice. One common short style of such a jacket was known as the

“Caraco” or “Pet-en-l’air.” Some jackets closed in front while others laced

and were worn with a stomacher.

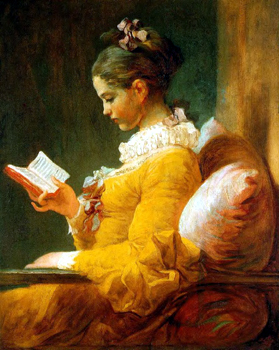

Ladies’ gowns could range from quite plain to

unbelievably luxurious and ostentatious. Cotton, silk and linen were all

used as were plain, striped, printed (usually with medium to large designs),

brocaded and embroidered fabrics. Most fabrics tended to have some weight or

stiffness to them at least until the mid 1780s when lighter weight silks and

cottons began to catch on. Lace and other trim as well as many types of

ornamentation were very common.

In the 1780s and 90s a completely new style

of round gown known as the “chemise gown” was popularized by imitators of

Queen Marie Antoinette of France. This dress was made of gathered fabric of

a light, flowing weight and consisted of skirt, bodice and sleeves. It was

initially mocked by many who declared that women were running about in their

undergarments (thus the name “chemise” gown) but it caught on quickly with

younger, fashionable ladies and proved to be the harbinger of the soon to

come Regency era styles.

The "sporty look" for the 18th century was the "Riding

Habit", an ensemble inspired by the uniforms of military officers. The coat

was much like a gentleman's regimental coat but tailored for a woman. It was

worn with a waistcoat, skirt, cocked hat and of course the proper

undergarments.

Undergarments:

Stays (aka Corset):

Thin or large, old or young, all ladies wore

them and you cannot have an accurate 18th century look without one. The

corset of the time was heavily boned and was tightly laced in the back for a

serious fit. It was worn under the gown but over the chemise. It was conical

in shape, completely unlike the “hourglass” corsets of the Victorian era a

century later. The purpose of the corset was to create erect posture and to

force the breasts up and together into a position known as “rising moons.”

During this period (in contrast to the late 19th and early 20th centuries)

for a fashionable woman to show much of her bosom (particularly with evening

wear) was not generally considered to be sexual or even immodest. It was

simply feminine; being a woman. But to reveal the ankles or legs was another

matter entirely.

Pannier:

Hoopskirts were a part of ladies fashion for

a long, long time. The terms hoopskirt, hooped skirt and hoops were all used

in the 18th century, but for the oblong variety we often utilize the term

“pannier”, which means "basket" in French. The pannier was to the 18th

century what the farthingale had been to the 16th and what the crinoline

would be to the middle decades of the 19th.

In the early part of the 18th century hooped

skirts were shaped like inverted cones and were not overly large. In the

1720s the prevailing style was large, round and dome shaped, much like what

was seen later with the hoops of the 1850s. In the 1730s the pannier shrunk

just a little and became a rounded oval with the slightly longer ends toward

the sides. By 1745 the pannier became a very wide oblong which was fairly

flat to the front and back. It continued in this basic shape for general use

until around 1770 when the round hoopskirt came back into vogue for a time.

The pannier was made of wood, whalebone or

reeds and was designed to hold out the upper petticoat and skirt, creating

width and therefore a horizontally oriented look. It was constructed to be

one wide article but an adaptation known as “pocket hoops” or “side

panniers” also appeared which featured a small structure of cloth and boning

on each hip connected by a waistband. The advantages of this variation were

less weight and the extra utility of actually being able to use it as

pockets for money, keys, a small mirror or what have you.

The width of panniers could range from modest

to extreme. Generally speaking, the larger panniers were reserved for more

formal occasions just as were the largest hoops during the mid-1800s. The

pannier maintained its popularity into the 1770s and then began to fade. In

the 1780s & ‘90s it was only being used for formal occasions and by 1800 was

utilized only for court apparel, the most formal style of all. Not long

after, the pannier disappeared altogether as the vertical emphasis of the

Regency era swept all before it and rendered the pannier an anachronism

which has never since returned to fashion.

Bumroll, Bustle, Rump Pad:

These items used for skirt support went in

and out of fashion for centuries. During this period such items were

typically made of carved cork or stuffing sewn up in linen or cotton fabric

with a tie coming out of each side. The article would be tied around the

waist under the skirt (and outer petticoat if not wearing a round gown) and

served to give them bulk and a lift to the rear (bustle, rump pad) or rear

and sides (bumroll). They were sometimes used by ladies not wearing a

pannier but could also be worn along with one for extra support to the rear.

When the chemise dress came into vogue during the 1780s a small bustle was

usually worn to give that fashion its characteristic rear lift.

Petticoats and Pockets:

In addition to the upper petticoat which with

most styles was meant to be seen, there were also one or more petticoats

underneath which were regarded as underwear. Cloth “pockets” were common.

These were a pair of flat cloth pouches sewn onto a cloth band which tied

around the waist underneath the outer garments. They were accessed through

slits in the sides of the skirt.

Shift (aka Chemise):

The shift was the bottom undergarment worn

under all others. It was usually of linen or cotton and in appearance was

something like a calf-length nightgown. A woman in only her chemise was

considered “naked”.

Accessories:

Shoes:

Much of what has been said regarding men’s

shoes applies. For instance “Shoes ... were usually of leather though fancy

shoes or dance slippers might be of silk (and could wear out in an evening

or two). Shoes were usually black or brown but were known in many colors,

especially among the wealthy. The buckle could be made of pewter, brass,

silver or gold. Very wealthy Europeans would sometimes have them encrusted

with diamonds and other precious stones.”

A difference would be that ladies’ shoes

tended to be narrower and were often more pointed in appearance as opposed

to the usual boxy look of the men’s. They were sometimes fabric covered and

could be decorated with ribbon, lace or other materials. Depending on the

occasion ladies could choose from the ubiquitous medium to high heeled shoes

with buckles, low or no heeled dancing slippers or even “pumps” which were

shaped very similar to the common modern variety.

Stockings:

These were long, coming up at least over the

knee and were fastened by garters around the leg. They were made from silk,

wool or cotton.

Hats, Caps & Bonnets:

Various styles were in vogue depending on who

you were and what you were doing at the time. The mob cap was as ubiquitous

for women as the tricorn was for men. It was made of cotton or linen

gathered to a band and covered much of the hair which was piled up

underneath it. Several styles of cloth bonnet were utilized including one

with long “lappets” down each side of the face and the “calash” which was

large enough to fit over high hair styles but was collapsible for ease of

storage when not being used. Fashionable ladies might wear a “cartwheel” hat

of straw, perhaps bedecked with silk flowers and tied under the chin with a

ribbon.

Both men and women typically wore some type

of headwear (whether wig and/or hat, cap, bonnet, etc.) during most of their

comings and goings. This was especially true outdoors not only for fashion’s

sake but also for the practical reason of protection from the elements.

Ladies in particular tried to avoid getting sun on their faces to a degree

which might darken their fair complexions. In contrast to the later 19th

century, both men and women commonly wore some type of headwear while

indoors as well. Men were even known to dance with hat on head or in hand

during a ball.

Hair and Wigs:

Hairstyles were for a time kept fairly close

to the head but then rose in height,

sometimes extravagantly so, particularly in the 1770s. Many cartoons of the time poked fun at

fashionable ladies for their ponderous coiffures. In the 1780s the

"hedgehog" style came in which was moderately high but wide as well and

often worn with a broad-brimmed hat. Women (like the men) also

commonly used wigs and hair pieces as well as white powder.

Fans, Jewelry and Cosmetics:

The fan was an important accessory for many

ladies and an entire “language” was developed in order to use it for

communicating from across a room. Jewelry of gold, silver and pewter was worn

and often included precious or semi-precious stones.

A white (“fair”) complexion was considered

very desirable and many ladies would utilize make-up to attain it. Beauty

marks of various shapes were in fashion for a time and cosmetics in general (particularly

rouge on the cheeks) were used far more than in the subsequent 19th century.

Many persons bore the scars of smallpox on their faces which undoubtedly

were an added incentive toward utilizing an artificial covering.

Even some men did so.

Note: This page and article are the

property of the author and may not be copied or reproduced except by express

written permission.

© 2001-2007 Lord Scott of We Make History